The Mis-Adventures Of A Road Warrior In The Fight Against Capital Punishment

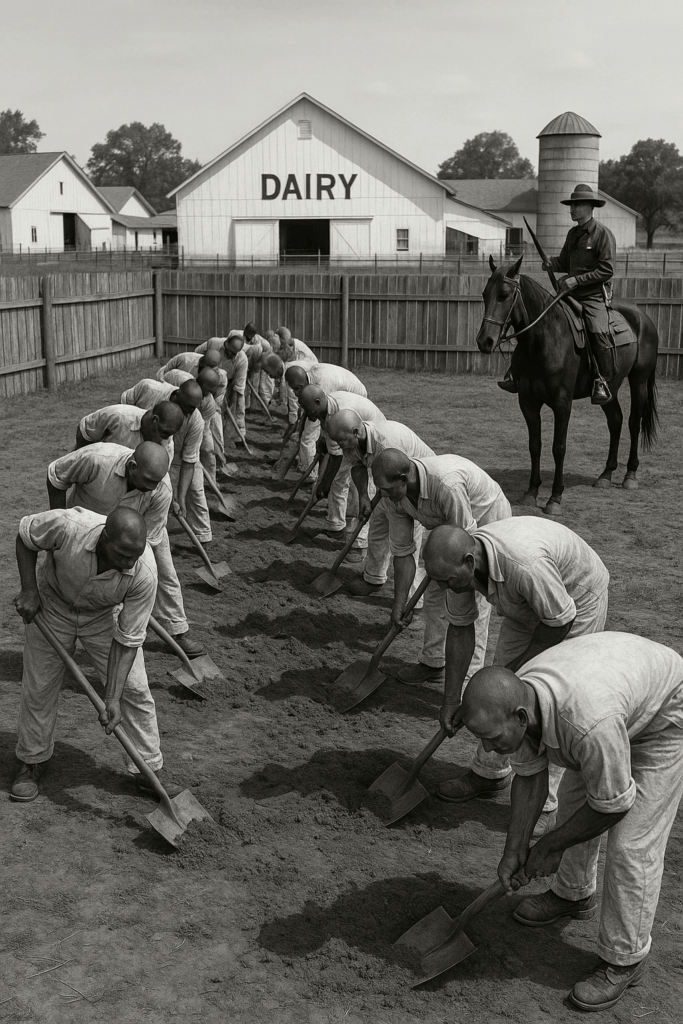

I write about the death penalty. Mostly in two states – Louisiana and Florida. But on the whole, everywhere in America. I also write a lot about prison as I have a whole lot of experience with being a prisoner there, and I like to write from the POV of experience and authority. 47 years of experience, I believe, qualifies me in that regard.

I happen to take executions personally, as I have been personally impacted by the deliberate and premeditated killing of a human being by an impersonal entity commonly referred to as a “state.” See my earlier story, published by HARVARD Inquest, “The Last Breakfast.” It is a coldly, well-planned and deeply impactful process that severely impacts families and turns them all into more victims. In fact, victims are used by this “state” as a promotional gimmick to justify their actions and actually promote their use as an example of “justice.” Florida goes a step further and has laws to shield everything about the process.

Execution of a criminal offender does NOT provide closure to a family member of a murdered victim. And, one of my personal heroes, who has an incredibly touching story, SuzAnn Bosler, used her forgiveness of the killer of her father to advocate for his clemency, even though he tried to kill her as well.

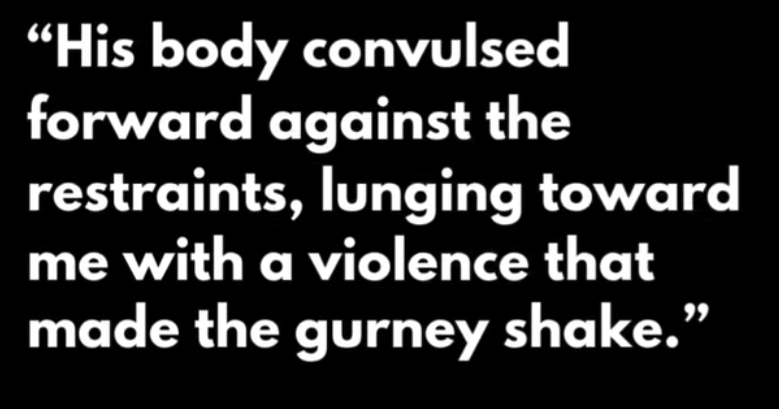

My personal interviews with SueZann left me heartbroken and weeping as she shared her story. Left for dead, she survived and eventually forgave the killer. She even hired her own attorney in an effort to save his life. Executions take a horrible toll on those who actually oversee and perform the executions themselves. The interviews with Allen Ault, the former Commissioner of Corrections for the State of Georgia, clearly tell us of this.

The lowly prison guards who participated in executions, underpaid and often underqualified to perform even the most menial of jobs, have been driven to desperate lengths. Because of a lack of support and trauma, they have often felt “less than,” and became “a murderer.” Some have resorted to suicide. Almost every single one of them changed their politics and their minds about executions after participating in one.

America has a wide variety of methods of killing people. The most common are (1) Lethal injection, (2) firing squad, (3) Electric chair and (4) nitrogen hypoxia suffocation. Nitrogen hypoxia is definitely an abomination, first used in Alabama, and later adopted in 3 other states: Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Oklahoma. Ohio and Nebraska have bills introduced as well to authorize the use of nitrogen to kill prisoners. All “Bible belt” states, all have MAGA “Christian” governors. Everyone is entitled to have their own view of Christianity; mine is that it is impossible for one to be both “pro-Life” AND a supporter of capital punishment.

All of the methods are horrific.

Let me tell you about my adventure with DeathPenaltyAction and Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty yesterday, Tuesday, December 9, 2025. It was an exhausting day, beginning with a calm awakening at 4:00am. I hastily drank coffee, answered a flurry of overnight emails, fed and walked the dogs, took a shower and shaved, went outside and smoked a cigarette, and came back in to prepare for the trip.

I went to Tallahassee with my friend, Robert, and was picked up at 9:30 by the wonderful Grace Ellen, Executive Director of Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. We went to the Good Shepherd Church, where we attended a prayer service for the soon-to-be-executed Mark Allen Geralds, the victim (Tressa Pettibone) and her family, and everyone in the chain-of-command involved in the execution. Grace, Abraham – one of the original founders of FADP – and SuzAnn spoke about forgiveness and the urgency of stopping executions and why they are so wrong.

We finished loading the trailer with shirts and signs, and then set off on our excursion to the office of Governor Ron DeSantis, the most prolific of all of Florida’s executing governors.

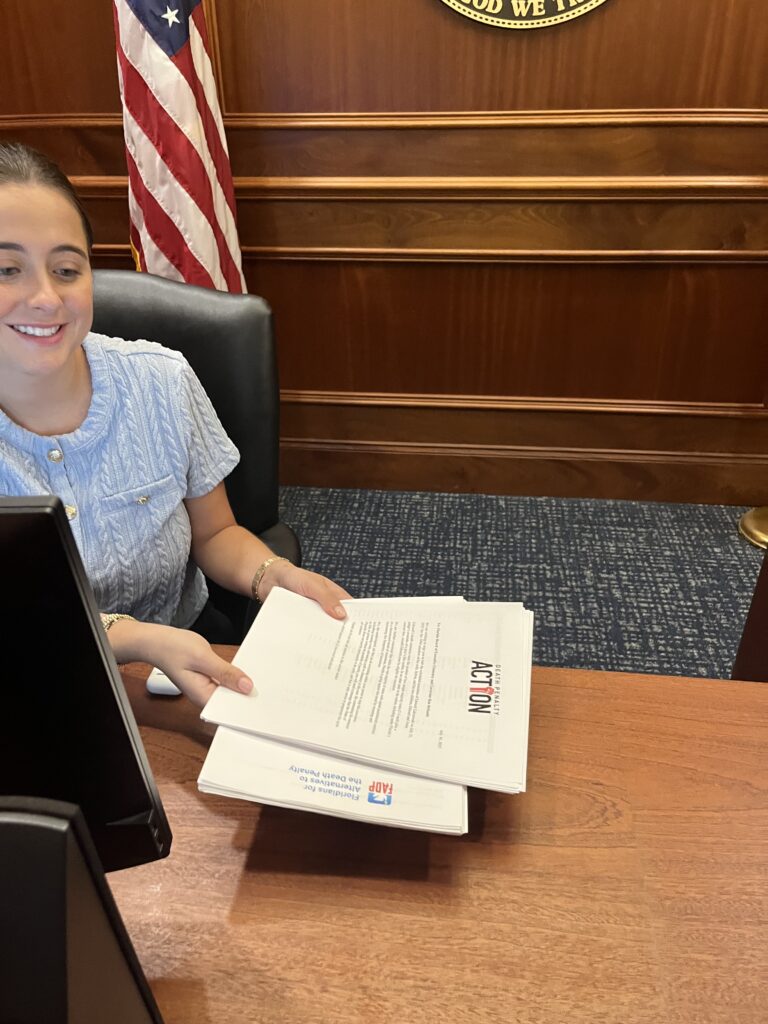

The media was waiting for us and we were videod, and gave our interviews, and proceeded to the Governor’s Office. Following a security search and wanding, we made our way to the reception desk where we interacted with her and she summoned someone to meet with us. The Governor, obviously, would not come out to meet and talk with us. This is the 18th execution he has ordered to be carried out this year. He cannot be proud of what he is doing, after all, but he did send a couple of very nice Constituent Services Representatives to meet with us, and again we pleaded our case and presented petitions from both groups.

Abe conducted the majority of the presentation explaining why we protest every execution and all of what is wrong with capital punishment. SueZann told her incredibly powerful story, and I touched on the wrongful conviction aspects and explained how Florida leads the entire nation in exonerations from their death row. Virtually every single exoneration from Louisiana involved one common factor – prosecutorial or official misconduct and illegal police conduct – torture, witness coercion or intimidation, and/or placing of informants in defendant’s cells who then gave false testimony to obtain convictions.

Later that evening, many who opposed the execution gathered at the state prison and held their service with Father Phil and the congregants from Our Lady of Lourdes (Daytona Beach). There were prayers and there was song and there was homily, followed by the ringing of the same bell – the same heavy cast bell that Abe totes with him everywhere he goes, to every execution, to every vigil.

The witnesses and the lawyers who attend the executions have told Grace that the ringing of the bell can definitely be heard inside the execution chamber.

Think about that. The solemn peal of the church bell, rung by protesters and the devout gathered beyond the prison walls, seeps through concrete and steel like a funeral hymn, impossible to ignore.

For the condemned, each toll of the bell and its’ echo becomes a sacred reminder of humanity reaching through the void, a gesture that they are seen in their final hour. For the executioners, it strikes deeper than their strict and formal protocols – an unwanted rhythm tapping at their conscience, breaking the sterile silence and the solemnity they rely on. Even the guards and warden feel the weight of it, the bell making the air heavier, as if time itself pauses to listen.

Finally, Abe and the others returned me to my home, my safe space, and rest from my journeys through the killing fields of Florida. There is another execution scheduled for just 8 days from today. Yet, we will not, we cannot be silenced. They must hear us.

Mark Geralds (Mark Allen Geralds), who was executed by lethal injection for the 1989 murder of Tressa Pettibone, was pronounced dead at 6:15 p.m. on Tuesday, December 9, 2025.

The execution took place at the Florida State Prison in Starke, Florida.

So, I need help now. This publication and sight is entirely reader-supported, and I can only continue doing it with your help. You can either buy me a coffee by clicking here:

donate to my GoFundMe, or you can SUBSCRIBE. I’ll be happy either way you choose – but, I really like the subscriptions because it means you’ll be around a lot longer. I’m dropping a button where you can do it very easily, or you can click any of the links above to help.