Left At The Altar

The interview meeting was not my first. It was to my knowledge, however, the first of its’ kind. I had been an Inmate Counsel (“lawyer” in the jailhouse sense) for a fair number of years and had encountered many entirely new and different – some might go so far as to say “unique” – situations. The guy sitting across from my desk I had talked to a number of times when I made my morning rounds of the tiers on Death Row. Just never at length, never without bars separating us, and never in such a tense moment.

His wrists were wrapped with solid stainless steel handcuffs threaded through the notorious ‘black box’ and his feet were shackled to his chair. Two security officers had brought him into the Legal Aid Office and strapped him in and cautioned him; “Do NOT fuck up! Act like you’ve got some sense now.”

At the time, I was kind of a hero, as I had just a few years before beaten the Warden, Burl Cain, in a huge lawsuit wherein I was portrayed as the hero and he the villain. It was not much of a stretch to frame Cain as a villain – he was wildly popular with Louisiana’s legislature – his brother, James David Cain (R) from Pitkin, Louisiana, was a legislator for some 36 years – and was often caught up in mildly scandalous affairs and various goings-on. Burl testified that I “used bad words,” and deserved to be punished for saying them. All I had said (in a letter to the FDA requesting an investigation into a private enterprise on prison grounds) was that it was “shrouded in secrecy and stinks of impropriety”

So he locked me up in solitary, I was threatened with being “shot while attempting to escape,” and various other forms of not-so-pleasurable treatment. However, thanks to a friend who smuggled a letter detailing my experiences to a federal judge, a volunteer lawyer who fought tooth-and-nail on my behalf (Keith Nordyke), and favorable public opinion, I eventually prevailed in a federal lawsuit. Instant fame amongst the convicts, instant landfall monies, and an instant target on my back from several different quarters.

I had fought my assignment to Death Row for some time. Burl Cain had summoned me to the A-Building late one night and asked me to take on the role. He explained why I was the perfect candidate for the job. I demurred with the best initial answer I could come up with at the moment – “Warden, how do you expect me to go in at night and lay my head down on that pillow and sleep, not knowing if I had correctly and effectively done everything possible to save that man’s life knowing that next week or the week after you’ll be the one to kill him?! I can’t do that.”

Well, as Wardens will do, he let me go with that, and then a week later Colonel Sam Smith called me in to an Internal Review Board and basically told me I had better take the assignment or…else. He said (off the taped record, of course) he had received instructions from Burl Cain. I abandoned my clients on the Civil Litigation Team and I accepted the assignment.

I had settled in fairly well and grown to learn most of my clients – all condemned to die by lethal injection – and become familiar with most of them and their needs. I had Shepardized cases for them, fetched and delivered law books to them, drafted motions on their behalf, filed public records requests for them, obtained DNA tests and located “lost” evidence in police files for them, and advocated with everybody on earth I could think of on their behalf.

This, however, was a beast of a different stripe. When I made morning rounds on the Tiers, Kevin S. had stopped me and thrust a piece of paper in my face. Shaking from fear or anger or worry or some emotion, he said, “Man, these mother-fuckers trying to kill me and I ain’t even got a lawyer!” Well, this wasn’t right or…was it? I mean, everybody on Death Row has lawyers, don’t they? Don’t they?

It was very simple – it was an Order from the 19th Judicial District Court in Baton Rouge (the state’s capital) setting his date of execution. The date that the State of Louisiana would calmly, methodically and purposefully kill him had been set.

But, to my way of thinking, it hadn’t been set in stone. And that’s the only thing that counts. You see, when a convict (especially an Inmate Counsel) thinks there’s a way to get past something, he’s going to find it. Now, it might be around it, over it, under it, or through it…but he’s going to find it.

So, after getting past my initial uneasiness at the way the meeting had started out, we got into the details. Kevin S. – a tall, heavily built and very dark Black man – had been convicted of the July 30, 1991, 1st Degree Murder of one Kenny Ray Cooper, a young guy working at a Church’s Fried Chicken. As he continued with the story, my skepticism began to wane. He told me that it was NOT an armed robbery, as the DA had presented it to the jury. It was actually a case of self-defense.

Louisiana defined 1st Degree Murder (Louisiana Revised Statute R.S. 14.30) at the time as:

“The killing of a human being:

(1) When the offender has specific intent to kill or to inflict great bodily harm and is engaged in the perpetration or attempted perpetration of certain listed felonies (e.g., aggravated kidnapping, rape, robbery, arson, burglary, assault, etc.),

OR

(2) When the offender has specific intent to kill or inflict great bodily harm and meets other aggravating factors.”

As Kevin unraveled the story to me, Kenny owed him money from a previous drug deal, and he had gone to collect after several failed attempts. An argument ensued, and Kenny pulled a gun and Kevin pulled his and they exchanged shots. Kenny died – Kevin survived. Now, Kevin was awaiting the horror of being killed by Louisiana for defending himself.

Before I go further into the story and my reliving of the moment, let me tell you a few things about Louisiana’s death penalty and its’ prosecution and application in Louisiana. Louisiana is inherently a racist state, and always has been. It has a rich and vibrant history of horrific racism. Even today, Louisiana’s justice system fights to maintain Jim Crow-era laws that are responsible for the mass incarceration crisis in the state, and which even now, threatens to dominate the nation in the numbers of prisoners stuck behind bars for the remainder of their natural lives.

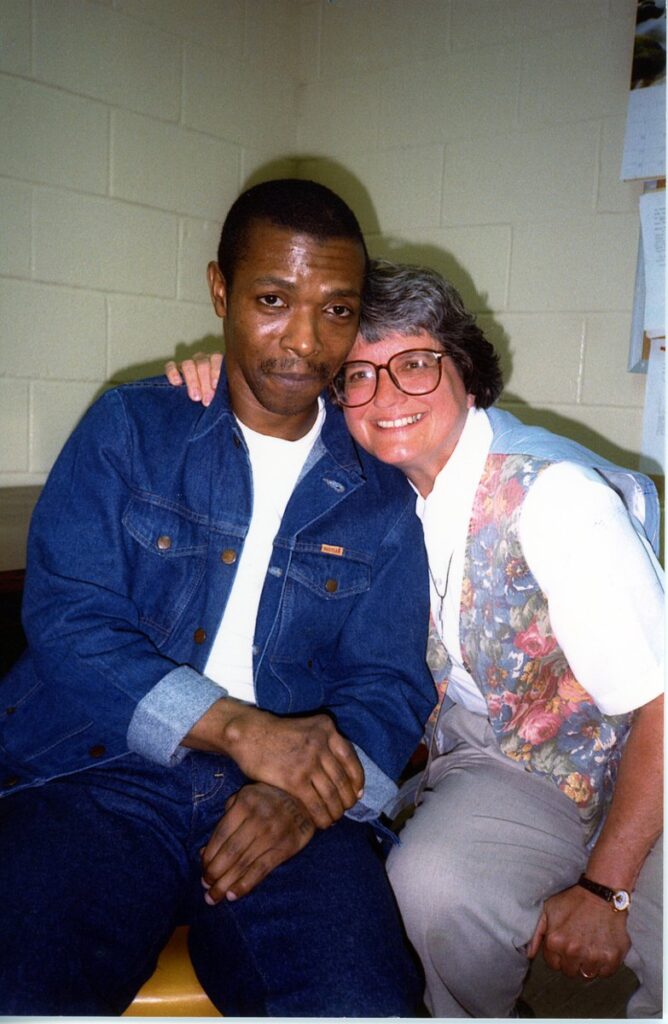

When I was in Angola prison (where I served 47 flat calendar years), at one point I was fortunate enough to meet the artist Debra Luster, while she was working on her beautiful exhibit One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana. As a wooden bowl maker and erstwhile craftsman, I participated in her project. This was only one of the myriad of experiences where I began to realize that Louisiana had a serious problem with racism and mass incarceration.

However, as I sat across the desk from Kevin on that day, these were all thoughts far from my mind. I was focused on one thing and one thing only: saving his life from being murdered by the State of Louisiana. It really made no difference to me whether Kevin was truly guilty or truly innocent – at moments such as this, innocence is never the point – the point is taking the next in a series of breaths.

Now, I believe I had told you that Kevin said to me, “…trying to kill me and I ain’t even got a lawyer!” Well, that wasn’t entirely correct, Turns out that he did indeed have attorneys appearing on his behalf. They just weren’t there. Turns out there was a big fancy wedding taking place in England, and his attorney was doing the most vitally important task of attending the wedding. Hmmm…balancing the scales between attending a wedding and getting a stay on Kevin’s case….I believe I would have chosen the latter. But, I digress….

I called Ms. Dora Rabalais, (Director of Legal Programs at Angola for 26 years) and explained the situation to her. At that point in time, we had a pretty good relationship because (secretly) she had admired my first battle with Warden Burl Cain, (wherein I wrote the now-famous “shrouded in secrecy” letter). At the conclusion of my case in Federal District Court, she had told me that I had brought credibility and strength back to the program. So, today, she was willing to help in this seemingly urgent matter.

She called the Death Row Warden who was in charge of both CCR (Close Cell Restriction) and Death Row, and I have no clue as to how the conversation went. I do know that it was only about an hour later that one of the post officers came to my office and told me that they would be bringing Kevin to the office in about thirty minutes. So, that’s how we came to be sitting across from each other, how I heard his story, and how the first-of-its-kind meeting was arranged, and how the next events took place.

Kevin and I talked for at least an hour or two and I told him what we would do. I would file for a Stay of Execution and go from there. I prepared it (my first one in such a critical matter!) using a Louisiana Formulary, and had it carried to Ms. Dora’s office where she faxed it to the court. As expected, a few hours later it was DENIED. I had already prepared an appeal of the denial and sent that back to Ms. Dora, where it was faxed to the Louisiana State Supreme Court. Baby stuff, right?

Maybe ‘baby stuff’, but for me, for Kevin, for everybody, it was huge. In times of clear pressure, Legal Programs was thriving and delivering on the promise of effective assistance of counsel substitutes to all inmates.

Under her leadership, Angola’s legal programs became a model for other states. States like Florida, Mississippi, and Texas adopted similar programs to enhance legal assistance for inmates without the need to hire additional attorneys.

Kevin eventually received his stay order. That night, if no other, I could lay my head down and rest knowing that I had done everything I could to help Kevin, and that it would not be the next week that Louisiana would kill him.

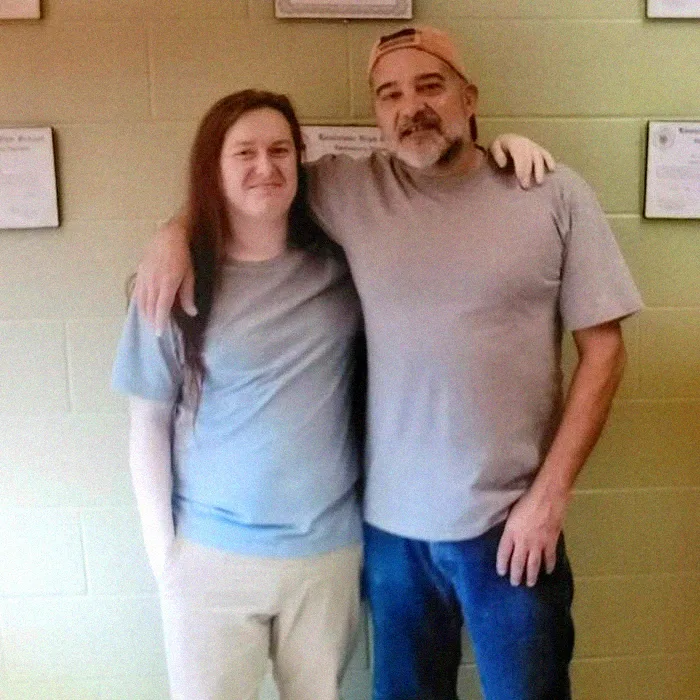

We had several more interactions over the next year or so, and I continued my work for Death Row, Treatment Center, and Infirmary Center inmate clients. Years later, I looked up one day in the chow line and Kevin was standing there – free from the promise of death. He had been re-sentenced and now had a LWOP (life without parole) sentence.

Sadly, though, my battles with Burl would resume some time later. We would get into a war over my accusations of financial impropriety and he would again send me to another institution. It was a harrowing experience to endure for what I felt was – again -doing the right thing. Ultimately, I prevailed again,

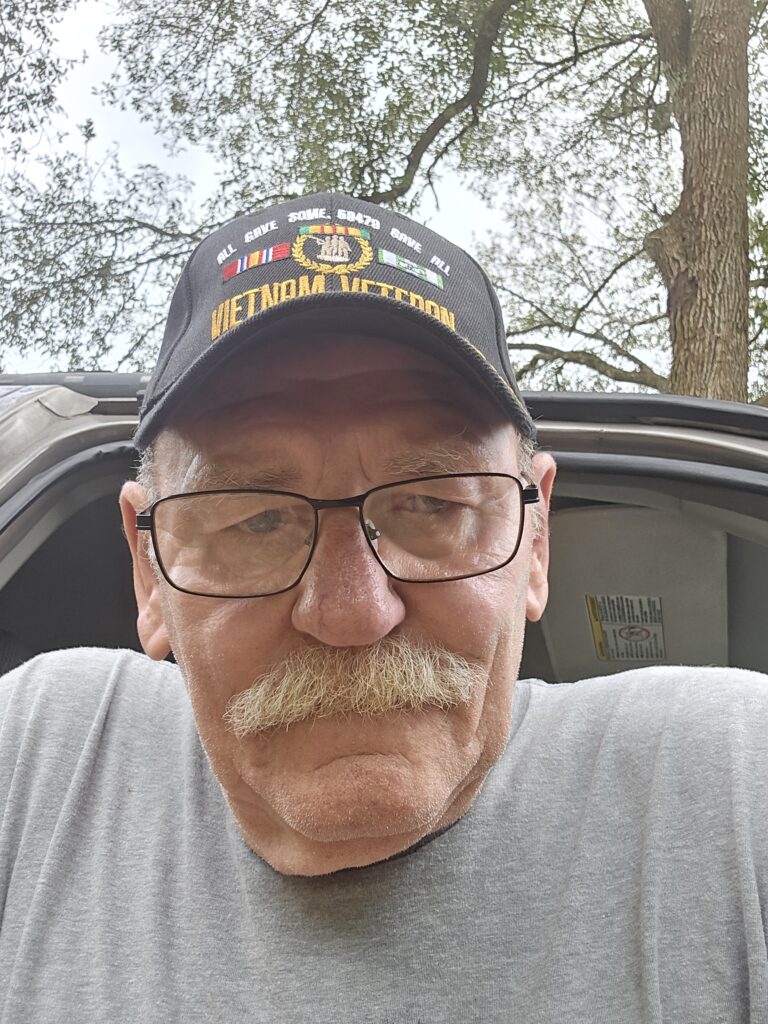

I have now been free for 781 days. I just turned 72. I’m living my best life. I hope you are too!

OR