It Ends In The Death House

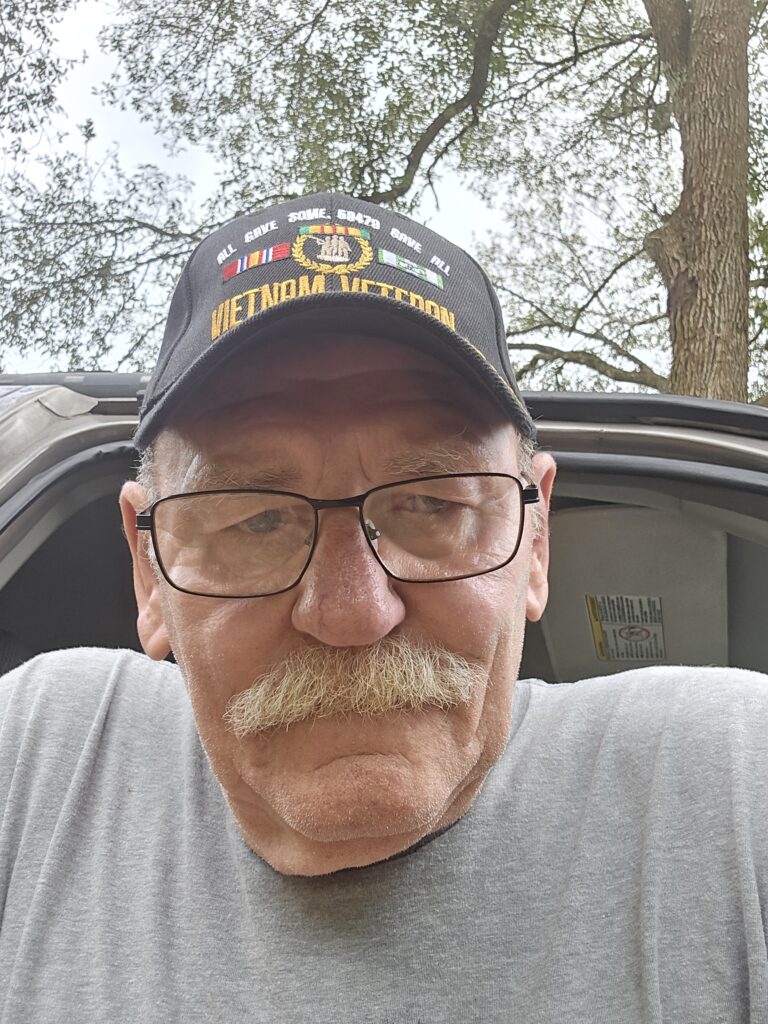

My trip to see the Governor – or the Floridian, His Excellency of Death – was eventful in that I met a wonderful Episcopal priest by the name of Reverend Susan Gage. Just as everything seemed as if it were going to go all the way off the rails, she showed up staring intently at my T-Shirt and Vietnam Veteran cap, as if God Himself had sent her to rescue me from my shortcomings. Made me wonder if God was either partial to Episcopalians or showing a bit of mercy to a blundering sinner.

In my very first solo mission for Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty and Death Penalty Action, I made a tremendous boo-boo. I made a miscalculation timewise and presented the dual Petitions for Clemency for Edward Zakrzewski 30 minutes early.

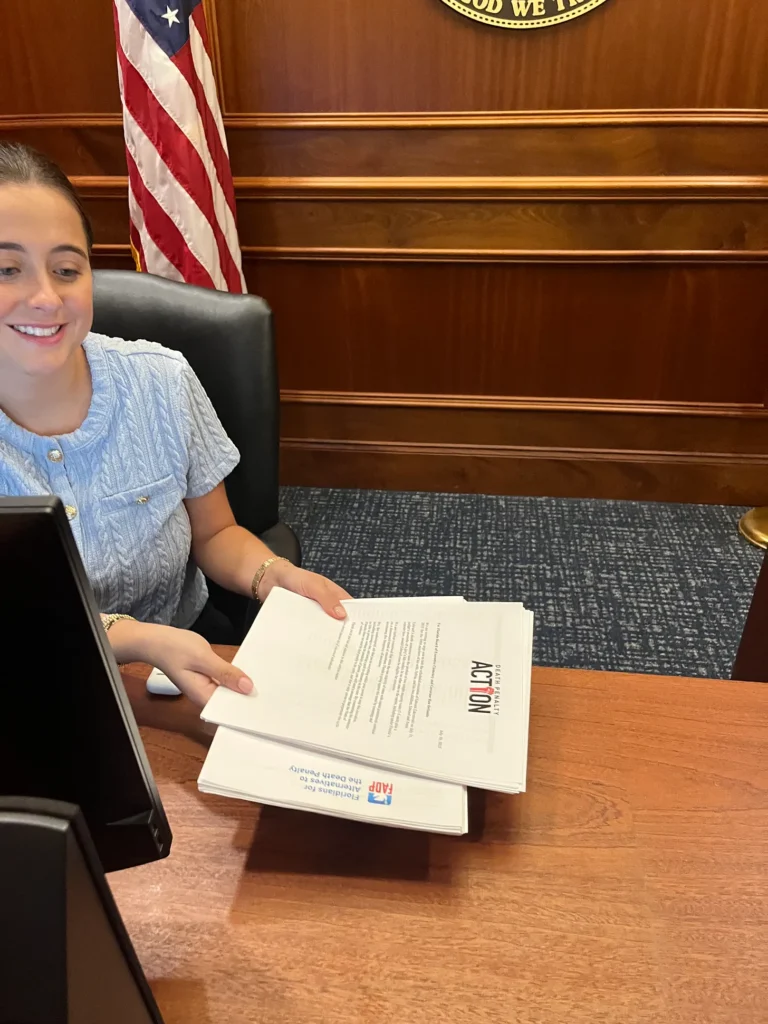

The only saving grace for me was twofold – no media timely made an appearance and I did have the foresight to take photos of my presentation to the beaming young lady sitting behind the imposing barrier of Reception. It appears that – as Susan patiently explained to me – it is very difficult to catch the attention of the media in Tallahassee. It seems as though executions have become so commonplace in Florida that they don’t even bother to show up any more unless, of course, there might possibly be an “illegal alien” lurking in the crowd for FHP and ICE to grab..

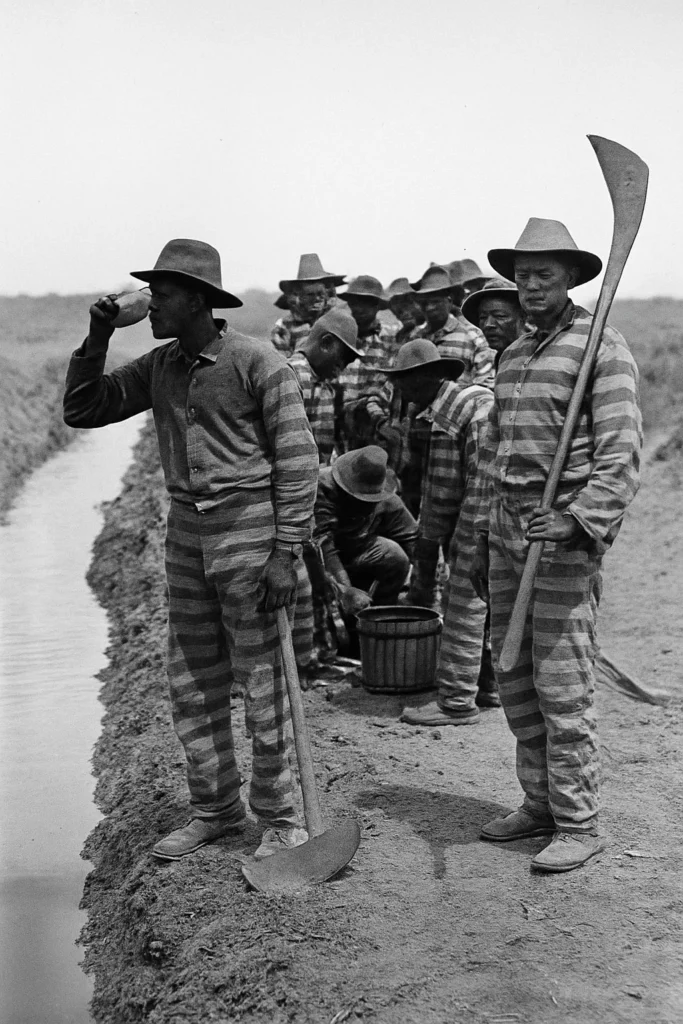

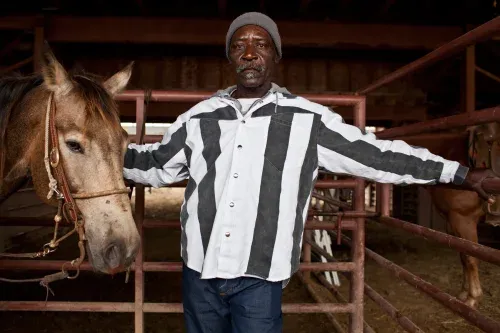

First though, before making my way haltingly to Reception. I had to traverse the Security barricades manned at the moment by no less than five big and burly armed officers, X-ray machines, bowls for metallic odds and ends and wands which they use to scan your person. Now, to be quite honest with you, this was an intimidating process; however, not one I am completely unfamiliar with. You see, I was in prison for 47 calendar years in Louisiana, so I am well-versed in intrusive – and abusive – searches.

This was neither intrusive or abusive, yet I knew the drill perfectly: empty your pockets, open the backpack, deposit phone(s) in the bowl, set laptop to the side, lift arms and follow directions, turning when told, and when approved gather everything back up. Ask for and receive directions. Simple, right? Absolutely. Traumatic and triggering? Absolutely!

It brought to mind all of the many, many times I had been shaken down in Angola by angry officers or scared officers or rookie guards who felt they had to make an impression. Though, honestly, they never impressed me. After a while you don’t let it affect you, just let them do their thing and hope for the best. Back in the game, we used the old trick of placing a hard-core porno magazine about 1/3 of the way down in our boxes, and it’d get them every time. They’d lock in on that and sit there for an hour slowly paging through the mag, and “forget” to shake us down and their lieutenant would call for them to go somewhere else. Then the new policies went into effect and porn was contraband, so we had to find new ways – and, of course, we did.

I got through this shakedown without incident, and was so relieved I thought I might pass out. Just a few short years before in prison, I had been fortunate to get in to a Shift Supervisor’s office without risking either a serious cursing out or lockdown or at the extreme, an ass-kicking and a stay in extended lockdown. They gave me directions and I gathered my belongings, stuffing pockets and lugging my backpack into place and sat off on this amazing journey. Once the necessary turns and corners were navigated, there it sat before me, this imposing hallway – the Pathway to Power.

It was an impressive Pathway for sure, a long and wide gleaming corridor of marble lined with gilt-framed oversized oil paintings of former Governors, some of whom went on to become US Congressmen. I am an Air Force Vietnam veteran and had the distinct pleasure of delivering a dispatch to a Brigadier General who was based in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) in much less grand quarters but who had equally impressive powers. The General had the power to summarily kill hundreds or thousands of people via a radioed order with no qualms, no hesitation, no regrets. This man at the end of this corridor had the power to kill only one at a time and solely with the stroke of a pen, but his actions would affect dozens now, and perhaps even future generations.

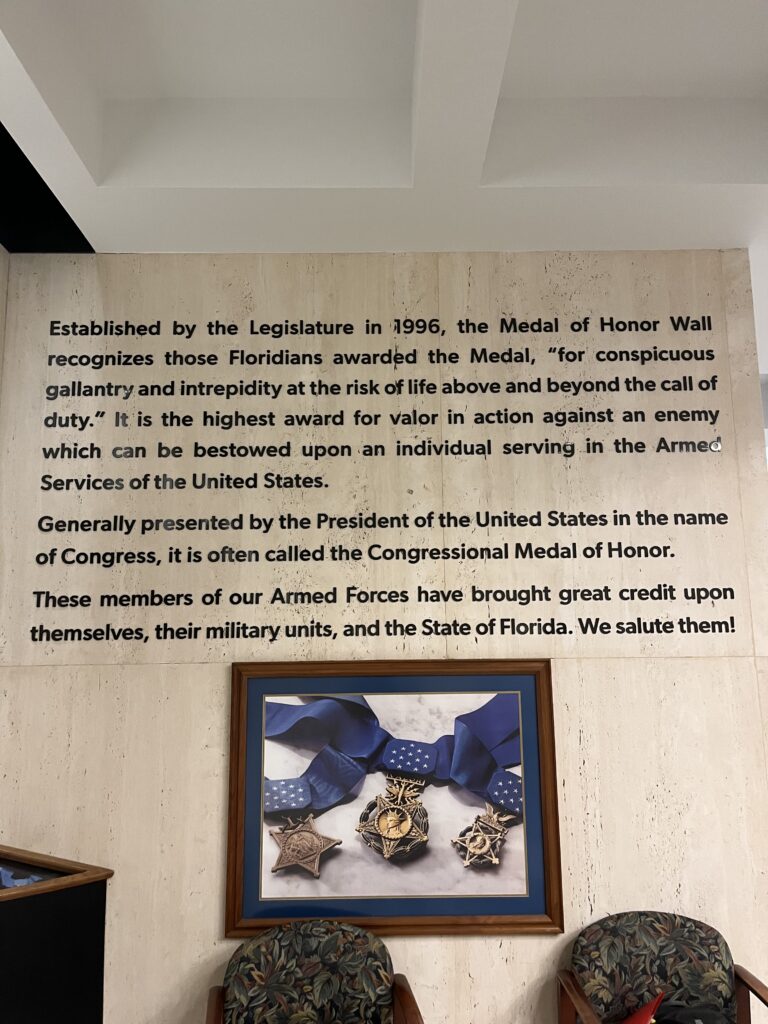

What struck me as I turned to enter this hallway was a section with an elegant display of plaques attached to the wall, marked “Florida’s Medal of Honor Recipients” in bold black lettering. There is an accompanying inscription explaining the Medal and describing in summation, “These members of the Armed Forces have brought great credit upon themselves, their military units, and the State of Florida. We salute them!”

Edward “Zak” Zakrzewski was an Air Force veteran. His military records consistently rated him as exemplary in conduct, appearance, and compliance with Air Force standards — both on and off duty. He was often described as a role model for others. He was no Medal of Honor recipient by far, but he did his job and was prepared to sacrifice himself in service to this country if called upon. His crime was horrific, but it was also completely out of character, and proof that he was plagued with emotional and mental burdens too heavy to bear.

These thoughts would not escape my mind as I crossed the final few feet into the opening to the sanctum. My heart was thundering in my chest as the lovely young lady behind the high desk asked if she could help me. Remembering my mission, I said very clearly and confidently

“I hope so, ma’am. I’m here as a representative of Death Penalty Action – a nationwide organization opposed to the death penalty – and Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. I have petitions from both groups with thousands of signatures calling upon Governor DeSantis to halt tomorrow’s execution of Edward Zakrzewski. We ask that he honor this man’s military service, and the fact that half of his jury wanted to spare him death. I would like to submit these petitions to him. Would you accept them and may I speak with him?”

To make it short, she accepted them with a smile and a few kind words and said that the Governor was not available. I thanked her and left, my heart rate slowing as I did until I came to the Medal of Honor display, and turned to ponder it again. It was tragic that politicians constantly harp on and on about how they “care for our Veterans,” and “honor their service” and “respect their sacrifices.” In reality, Veterans are expendable on the fields of battle and in everyday life. Why else would there be thousands of veterans battling addiction, sleeping on the streets and in whatever shelter they can find? Why else would vital physical and mental health services be cut and benefits denied?

Edward Zakrzewski sought treatment and sought help for his demons. He remained deeply remorseful for many years. Five members of his jury voted for life instead of death. The judge overrode their decision. If he stood trial under today’s laws in Florida, he would be ineligible for execution. Edward Zakrzewski deserved mercy, and hardly merited a moment’s thought as DeSantis’ pen scrawled across the warrant calling for his execution.

Florida this year has carried out more executions than any other state, while Texas and South Carolina are tied for second with four each. A 10th execution is scheduled in Florida on Aug. 19 and an 11th on Aug. 28 under death warrants signed by Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Florida is setting records already – it’s just now August 1 – and not in a good way.

My mission was complete, if not a success. RIP, Zak.