A Bloody Encounter and An Angry Doctor

There were a whole lot of times when I was in Angola that I thought I had reached the end of my rope, that I just couldn’t go one more day, that I couldn’t take one more work call. This is just one of those times. Fortunately, it worked out so that I was able to live to serve a lot more of the 47 flat calendar years I did in that hellhole.

Medical care at Angola has ALWAYS been horrible. It was horrible in the 70’s, and has gotten only slightly better, and only because of court-ordered changes.

- Constitutional Violations:Federal judges have ruled that Angola’s medical care is not only subpar but also constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

- “Callous and Wanton Disregard”:The court found that prison staff and administration have “callous and wanton disregard” for the health needs of the incarcerated population, leading to a pervasive state of illness.

- Specific Deficiencies:Deficiencies were noted in:

- Clinical care (including sick call and medication management)

- Inpatient/infirmary care

- Emergency care

- Specialty care

- Decades of Neglect:Evidence shows the state has been aware of and failed to address these deficiencies for decades.

So, it was well on into my early years in Angola when I came very close to seeing the end of my sentence. This was a period where virtually everything was in short supply. Repair of anything was an unrealized fantasy, silverfish and cockroaches ruled the dormitories. If something in the prison was broken, the attitude was pretty much, “Well, just paint it.” I was still dealing with the ugly grind of field work in the Farm Line. Camp A had its’ own farm line and I had been toting that standard for a couple of years.

Long days of backbreaking and mind-numbing labor, most of which was “make-work,” just something to work the hell out of you and make you bone-tired. ALL of it took a toll on you, mentally, emotionally and physically.

I’d already been down a few years at Angola, staring at an LWOP, and by then the days just started running together. I was housed at Camp A, which carried its own kind of crazy — a different vibe, a harder edge, like the walls themselves had soaked up all the madness and spit it back out at us. It used to be known as the “White Elephant,” and had a bloody history tied to it like an anchor.

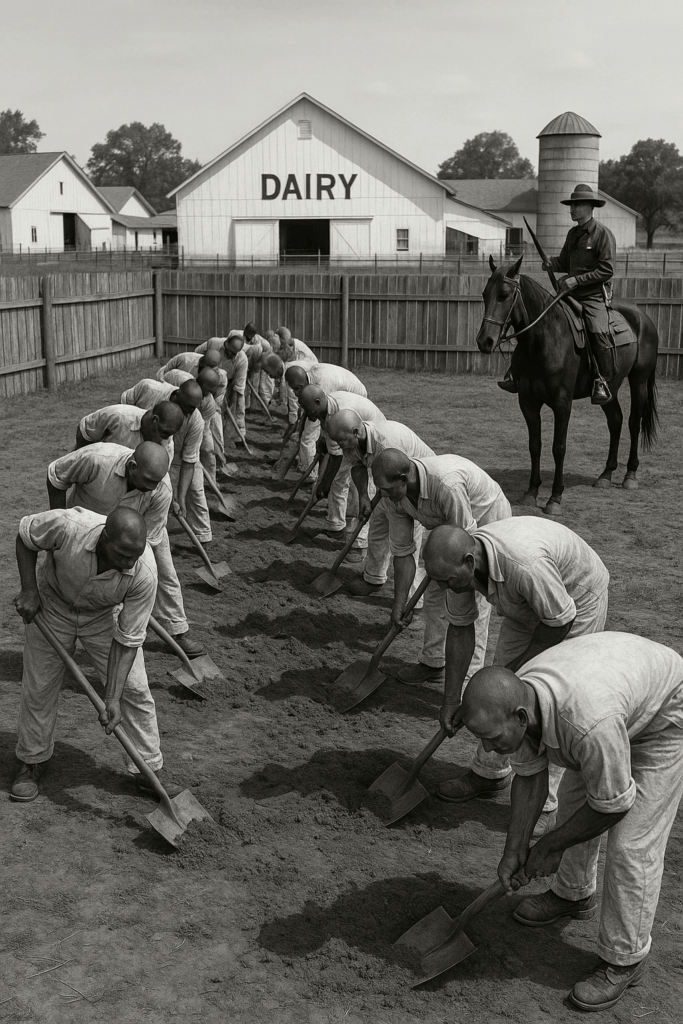

They had us working Line 2, and that morning my squad was sent behind the Camp A Dairy. What we did was called “quarter-draining,” which was to dig little paths through the pen for drainage. The spot was called the grab pen — where the cows got bunched up before they were herded inside to be milked. The ground out there stayed slick and nasty, churned up mud mixed with piss and shit from all those cows standing around too long. Every step was a fight not to lose a boot, and the smell of it hit you deep in your throat, like you couldn’t ever wash it out.

We were out there in that mess, maybe 15 of us, just moving slow, trying to keep from slipping. Nobody wanted to bust their ass in that slop. The free-man boss sat up on his horse, watching us like he always did, not saying much, just chewing on his toothpick like he owned the whole damn world, occasionally spitting tobacco juice around the toothpick. Every once in a while just in case anybody thought he wasn’t paying attention, he’d spit out a stream of juice and snarl out an oath – “Get your cracker ass on and get to digging my fuckin’ quarter drains!”

The cows weren’t in any hurry either. Big, heavy bodies pushing against each other, lowing, shitting, pissing, making the ground worse with every step. You’d try to guide one along and another would swing its head at you, big floppy ears catching the air close enough to make you flinch. Out there, you learned real quick that you weren’t the meanest thing in the pen. It was mostly the buzzing blue flies that were the meanest. They landed on all that piss and shit, buzzed all around you and then landed on you and you got chills running up your spine.

I remember standing there, sweat running down my back, mud and cow shit creeping over the tops of my boots, and thinking: this was my life now. Not a season, not a stretch, but forever. Every morning another field, another pen, another stink that clung to me long after I left it.

The grab pen was its own kind of trap. There was nowhere to stand clean, nowhere to breathe easy. Every time the sun came up, that steam would rise off the ground — piss and shit cooking together — and it would wrap around you, stick to your clothes, crawl up into your nose until you almost couldn’t taste anything else.

The men didn’t talk much out there. Maybe a curse when a boot got stuck, or a laugh if somebody damn near went down face-first. But mostly it was just the sounds of the cows and that steady creak of the boss’s saddle as he shifted on the horse. His rifle lay across his lap, casual, like it wasn’t even meant for us — but we all knew it was.

After a while, you stopped noticing the smell, stopped noticing the mud pulling at your legs. What you couldn’t stop noticing was the weight of it all. The fence around the pen. The fence around the farm, the fence around the camp. The fences inside your own head.

Not long before this, they’d issued me a new pair of brogans. Heavy, ankle-high stiff boots meant for dry land, not for the swamp of a grab pen. First day I laced them up, they already felt wrong, cutting at my ankles, rubbing at my heels. But you don’t complain about boots in Angola — you just wear what they give you and keep moving.

What I didn’t know was that a little piece of rock, maybe no bigger than a sliver of a fingernail, had slipped down inside one of my brogues. The mud and water kept my socks wet all day, and the rubbing started carving at my foot without me realizing it. By the time I did, the skin was scraped open, raw. Out there, raw skin didn’t stay clean for long.

Every step I took in that slop, the mix of piss and shit worked its way into that cut, deeper than I wanted to think about. At first it was just sore, a little sting when I put weight on it. But the next day, I woke up with my whole foot throbbing. By noon, I could feel it climbing my leg, burning inside me in a way that had nothing to do with the sun overhead.

Two days in, it was bad. My foot was so swollen I couldn’t pull my boot onto it. My fever kept climbing, and my body felt like it was shutting down one piece at a time. I was dizzy, weak, couldn’t keep food down, couldn’t even make myself care about eating. My skin was hot, but I was shivering inside. I knew something was seriously wrong, but I was too sick to do much more than just drag myself through it. By nightfall, my leg had angry-looking red streaks criss-crossing and running all the way up to my waist. I knew this was bad, just not how bad.

I finally hit the point where I couldn’t tough it out anymore. It went against everything in me to do it, but I had no choice — I had to call on the free man. That was the CO over the dorm, the one who held the keys and the clock, and usually couldn’t care less if you dropped dead in your rack.

I staggered up to the front of the dorm and started banging on the door, hard as I could manage. The sound echoed, but it still felt like it took forever before he showed. When he did, he looked pissed, like I’d interrupted his cigarette break or his crossword.

I told him I needed help. He laughed it off, told me there wasn’t a damn thing wrong with me that couldn’t wait until morning. Basically told me to get fucked, and started to walk away. But I wasn’t letting go — not this time. I leaned on the bars, kept insisting, told him I was serious.

Finally, I yanked my pant leg up and showed him my foot, swollen and purple, and then I pulled my shirt up so he could see the angry red streaks running all the way up my side. I was shaking, sweating through my clothes, barely able to stand upright.

That got to him. His face didn’t go soft, exactly, but something shifted. He stood there looking at me for a long beat, then muttered that he’d go see the lieutenant. Then he disappeared, and I was left holding myself up on the bars, praying he didn’t just forget about me.

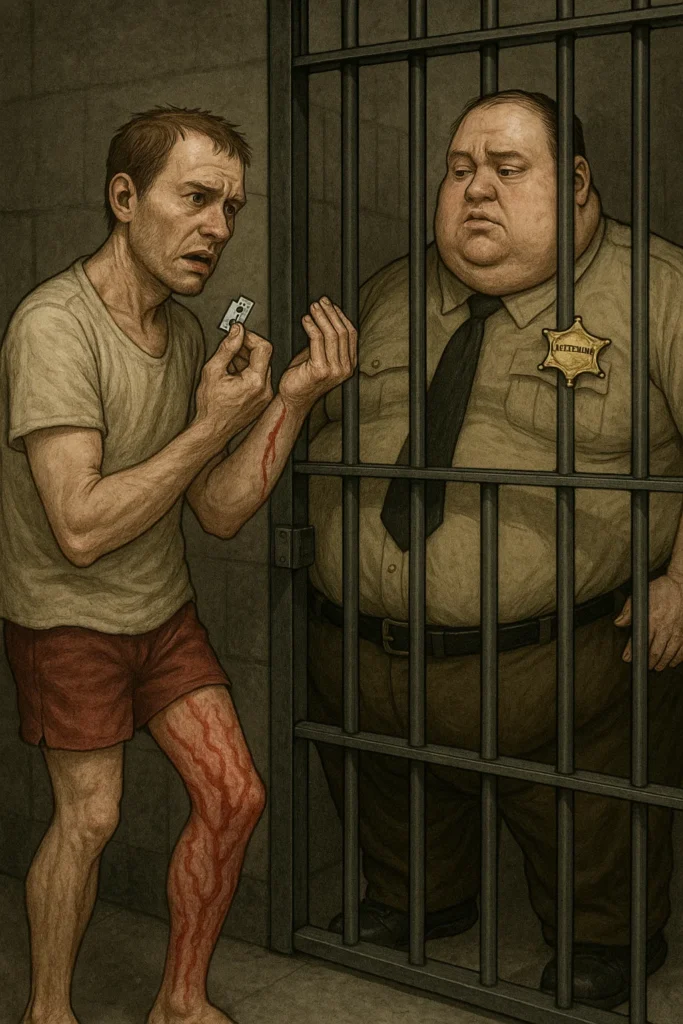

About twenty minutes later, Lieutenant Hart finally showed up. Everybody called him Big Daddy. He was a mountain of a man — had to be pushing four hundred and fifty pounds easy — and he moved like it hurt him just to be upright. Each step was a slow roll, like the floor dipped under him.

He came up on me, eyes small in that big red face, and asked what was going on. I told him. He looked at my foot, at the streaks crawling up my leg, and just shrugged. Told me to wait until the next day, like I’d been making a fuss over nothing, like I was mad he took my cookies or something.

Something in me snapped right then. We started going back and forth, him gruff and dismissive, me desperate and sick and not caring anymore. My head was burning but my hands were steady. I pulled out a little razor blade I’d been holding onto, laid it across my arm, and dragged it just enough to open the skin so he could see the blood. Then I laid it back on my arm and stared at him.

“You can either send me to the hospital for my leg,” I said, voice shaking, “or you can send me to get this motherfucking arm sewed back on!”

Big Daddy froze for a second, staring at the thin line of blood on my arm. His face twitched like he couldn’t decide whether to roar at me or grab me. Then he cursed under his breath, spat tobacco juice at the floor, and barked for two rank-and-file night guards. They came stomping up the stairs and in from the corridor, both of them in sweat-stained khakis and scowls like permanent scars.

“Take this fool to the infirmary,” Big Daddy snapped. “Now.”

They didn’t handle me gently. Each one took an arm and yanked me forward hard enough to make my knees buckle. I stumbled between them, half-dragged down the hallway, my foot throbbing so bad I couldn’t feel the floor. The guards muttered and cussed the whole way—about being pulled off their posts, about “malingering,” about “another dumb-ass convict trying to milk a sick call.” Their grips were iron, fingers digging into my arms, but I didn’t care. The only thing keeping me upright was the thought that I was finally, maybe, headed somewhere I could get help.

We reached the infirmary at the Treatment Center — a low-lit room with chipped paint and the stale smell of antiseptic. The night duty doctor was already there, a big man with a gray beard and a face like carved stone. He didn’t look up at first, just kept scribbling something on a clipboard. “Put him on the table,” he said flatly.

The guards shoved me onto the exam table, and I swayed, gripping the edge with white knuckles. The doctor finally looked up, and when his eyes hit my leg, his expression changed fast. He dropped the clipboard onto the counter with a clatter.

“Jesus Christ,” he growled, pulling on gloves. “How long has it been like this?”

I mumbled something—two days, maybe three—but my voice was thin. He didn’t even answer. He yanked my pant leg up, peeled back the filthy band of my sock, and let out a sharp hiss of breath. Red streaks like lightning bolts raced up my calf, across my thigh, and vanished under my shirt. He lifted the hem and saw the rest. His jaw tightened.

“You’re about eight hours from this hitting your heart,” he snapped, turning on the guards. “And when it does, he’s dead. You understand that? DEAD.” His voice cracked like a whip. “This is a severe septic infection—blood poisoning. This man needed treatment yesterday.”

The guards shifted uncomfortably but didn’t say anything. One of them muttered, “He didn’t look that bad—”

The doctor whirled on him, eyes blazing. “You idiots can’t see a man dying in front of you? If he’d waited until morning, you’d be zipping him into a body bag!”

He slammed a drawer shut and started pulling supplies out—IV kit, antibiotics, things I couldn’t even name. His hands were fast but steady. “We don’t have time for this place’s nonsense,” he barked. “Call the control center and tell ‘em he’s going to Charity Hospital. Get a van ready. I don’t care who you wake up or what strings you have to pull. He’s going out tonight.”

“No ambulances at this hour,” one of the guards said.

“Then get the van,” the doctor snapped. “I’ll ride with him if I have to. Move!”

They bolted out. The doctor turned back to me, his eyes softer now, but only just. “You’re damned lucky you made it here when you did,” he muttered. “Another eight hours, and you wouldn’t have had a prayer.” He jammed the IV needle into my arm with practiced speed, hooked up a bag of clear fluid, and pressed a mask over my face.

The last thing I remember was the cool rush of liquid sliding into my veins and the smell of disinfectant, the doctor’s rough voice still echoing in my head: “Eight hours from your heart. Eight hours from dead.” Then the room tilted, and the lights blurred as they wheeled me out toward the waiting van and whatever came next.

Leave a Reply