This is an exhausting journey to be on, this fight against the death penalty. Exhausting, but – yes, interesting. Interesting in that every case is similar yet different. Interesting in that we’re presented with so many different personalities as we trudge along this path, sometimes forward and sometimes walking backwards, sometimes being pushed backwards and off the path. The one consolation is that we never walk alone. The anti-death penalty community is a small but committed and tightly knit one, with friends and allies in the sometimes unlikeliest of places and at unlikely times.

He walked the cracked asphalt roads outside the state prison, his battered shoes softened by the hours of pacing with a placard in hand. The words, scrawled in uneven marker paint—”Mercy Is Justice” — alternating with — “Stop Gas Executions”, or “Execution Is NOT The Solution” — had long since grown heavy to him, acting more as a shield than a message. His voice was hoarse from chanting into the indifferent and non-hearing wind, yet he persisted, tracing the same worn path past chain-link fences, concrete walls, and rows of armed guards whose eyes followed him with cold amusement. Every step was a ritual, a prayer against the inevitability of a clock ticking toward midnight executions or stopping short at 6:00, praying for a stay, a reprieve, a gift from God.

Yet along this lonely march, allies emerged from unexpected shadows. A prison nurse, weary from tending to men who would not live to grow old, stopped to press a bottle of water into his hand, whispering, “I wish I could say this for myself, and say it out loud – but I must consider my retirement and my future.” A grizzled ex-guard—once his adversary across the fence—fell into step beside him one evening, muttering that the killing had rotted away at his soul until he could no longer bear it. Even a mother in mourning, her son murdered years ago, came not to condemn but to stand silently near him, carrying her grief as testimony that justice need not be sharpened to a blade.

The path wound longer than the road itself, each footfall carrying him deeper into a strange fellowship stitched from fragments of guilt, sorrow, and defiance, all pieces to a puzzle. He realized he no longer walked alone but at the head of a procession of unlikely companions, all tethered by the same invisible weight. Though the state’s machinery ground on, implacable and deaf, the protester found that his path was no longer only protest—it was pilgrimage. And on that path, every voice beside his own turned the solitary chant into something approaching a chorus.

These are the ghosts that join us. These are the voices that urge us on forward, to not give up the fight. To fight and protest for every death carried out by the State, for every murder committed by the State. We will not give up this fight.

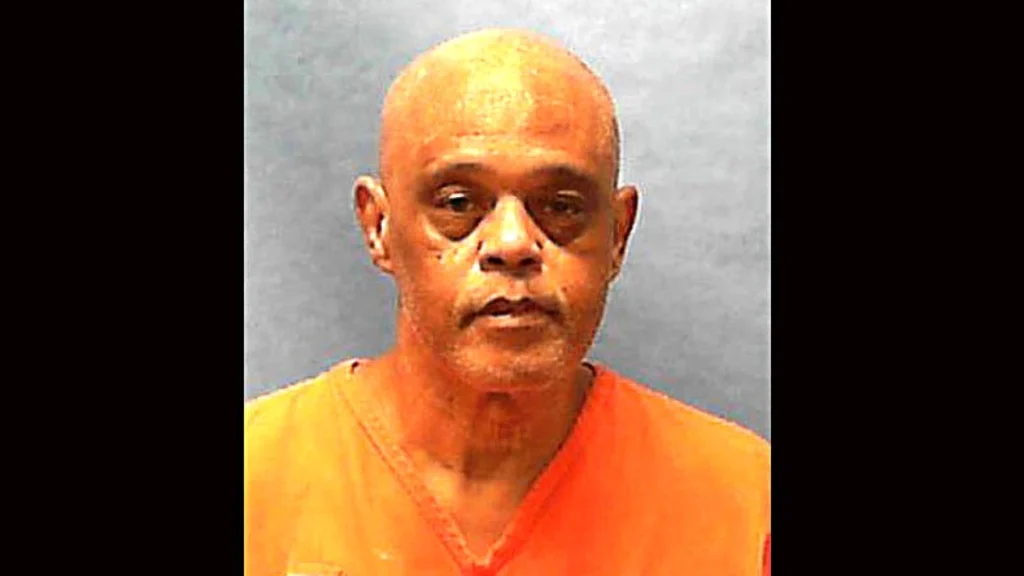

Condemned killer Ralph Leroy Menzies, arguably has one last chance to avoid a firing squad execution by appealing to the Utah Supreme Court.

Repetitive application? By far. Chances of evading execution? You pick the numbers…

On Thursday, the state’s top court heard arguments over whether Menzies’ upcoming execution should have been halted pending appeal, and whether a lower court judge should have ordered a new competency evaluation once his attorneys disclosed his dementia had gotten worse.

That same judge previously found Menzies competent to be executed for the 1986 murder of Maurine Hunsaker, who was taken from her job at a Kearns gas station, tied to a tree and her throat was slit.

“Mr. Menzies has a progressive disease. He is always getting worse,” his attorney, Lindsey Layer, argued to the justices.

He sat in the narrow cell, its walls painted the color of old bone, staring at the blank steel door as though it might one day speak to him. His hair had thinned to wisps, his body frail beneath the coarse prison uniform, but his eyes—clouded, drifting—held no recognition of the years or the sentence hanging over him. Once, he had argued with lawyers, shouted at guards, clung to scraps of appeals and promises. Now he no longer remembered those battles. He asked instead when his mother might visit, though she had been buried for half a century, or whether he could go home soon, confused why they kept him here at all.

The warden visited, speaking carefully, slowly, about the scheduled execution. The condemned man nodded politely, then asked whether dinner would come on time. He did not know what a firing squad was, nor why so many solemn faces gathered to watch him shuffle down the corridor during rehearsals of protocol. To him, the preparations were rituals without meaning, the men with rifles perhaps soldiers in some far-off war that never touched his understanding. When guards whispered “he doesn’t even know anymore,” he only smiled faintly, humming a song half-remembered from boyhood, the words lost to the ravages of time.

“If this particular illness is progressive, it changes all the time, how do we not end up in this situation repeatedly?” asked Justice Paige Petersen.

“With this particular illness? That is true,” Layer replied.

Justice Diana Hagen questioned where the line is for a defendant to understand the nature of their crime and the punishment being handed down and what qualifies as a substantial change. Layer told the Court that Menzies’ circumstances have substantially changed.

Chief Justice Matthew Durrant raised the issue of some prison phone calls that Menzies had made that prosecutors submitted as evidence that he is competent.

“He does seem to understand who he’s speaking with, he’s giving appropriate responses,” Chief Justice Durrant said, later adding: “How does that level of understanding, let’s say, figure into the legal standard for competency to be executed?”

But Layer argued it did not show the whole picture, where Menzies struggled to even make some phone calls to his lawyers and others.

Decades of waiting had stripped him of context, leaving only a fragile shell of routine. Each day was measured by trays of food slid through a slot, by the rattle of keys at dawn and dusk. Death, as the state decreed it, was no longer real to him; he could not grasp it, could not fear it, could not prepare for it. And yet the machinery of law continued grinding forward, as indifferent to his forgetfulness as the concrete floor beneath his feet. For him, there was no looming end—only another morning, another question, another fragment of memory slipping into silence.

“He’s clearly struggling, he’s not able to complete those calls,” she told the Court.

Assistant Utah Attorney General Daniel Boyer argued that not enough has changed to justify a new competency evaluation.

“The defendant must specifically allege a substantial change in circumstances, the petition must be sufficient to raise a question about the inmate’s competency,” he said.

Utah last executed prisoners by firing squad in 2010, and South Carolina used the method on two men this year. Only three other states — Idaho, Mississippi and Oklahoma — allow firing squad executions.

Ralph Leroy Menzies, 67, is set to be executed Sept. 5 for abducting and killing a Utah mother of three, Maurine Hunsaker, in 1986. When given a choice decades ago, Menzies selected a firing squad as his method of execution. He would become only the sixth U.S. prisoner executed by firing squad since 1977.

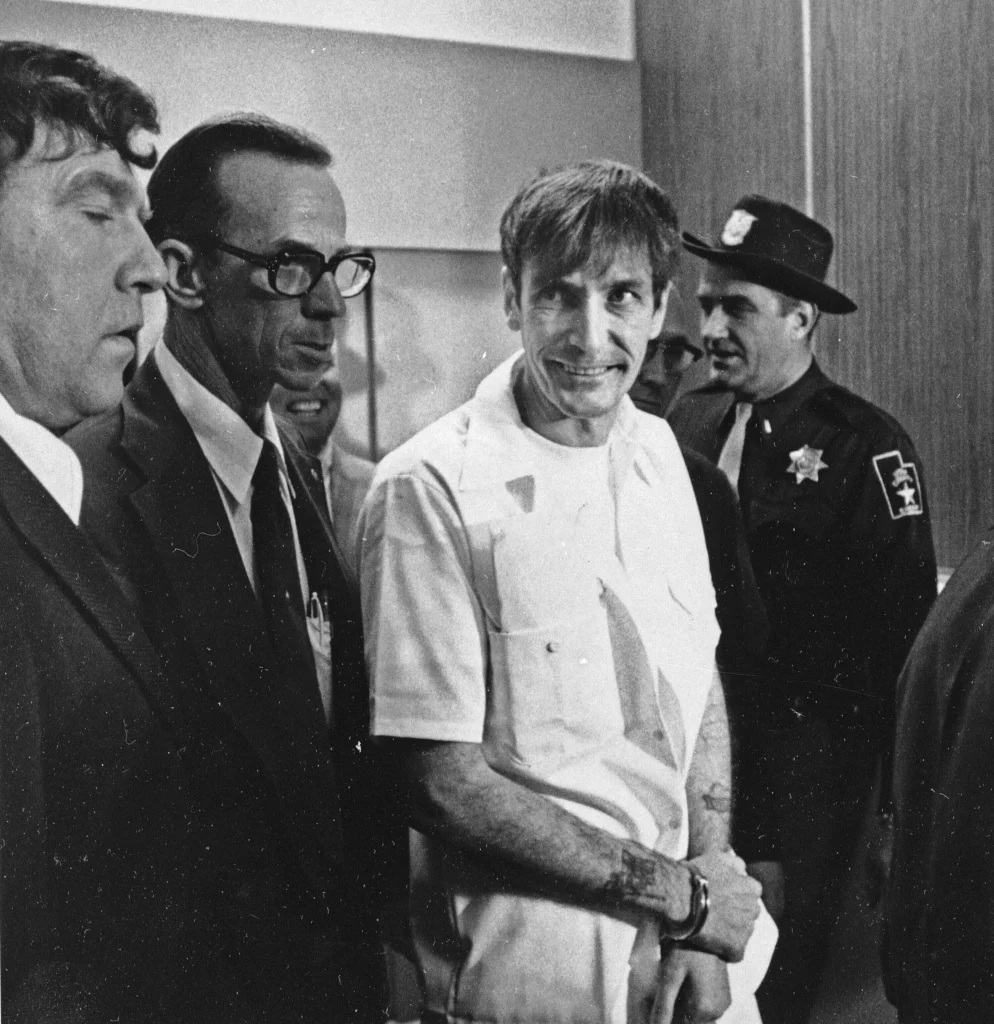

The most notable, perhaps, was Gary Gilmore about whom the book, “The Executioner’s Song” was written by bestselling author, Norman Mailer.

Utah has a particularly long and bloody history with firing squad executions. Utah’s history with firing squad executions dates back to its original statutes, which allowed it as a method of punishment alongside beheading and hanging. The state has historically been a leader in its use, especially in the modern era following the reinstatement of capital punishment in the 1970s.

Utah was the first state to resume executions after the national moratorium with Gary Gilmore’s execution in 1977, and remained the only state to carry out a firing squad execution in the modern era until the 2010 execution of Ronnie Lee Gardner.

Executing someone with dementia is problematic because competency laws require a prisoner to fully understand the punishment they face (to be executed), which dementia impairs. The primary concern is that a person with dementia cannot rationally comprehend their execution or the reasons for it, rendering the execution unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. The firing squad execution itself adds to the concern, as it potentially increases the risk of suffering and error.

Legal and Constitutional Issues

- Incompetency:Federal and state laws mandate that a death row inmate must be competent, meaning they understand they are facing execution and the reasons for it, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

- Ford v. Wainwright:The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that executing someone who doesn’t understand the reasons for their punishment violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

- 2003 The Utah Legislature unanimously approves a bill that prohibits the execution of those with intellectual disabilities.

- Attorneys for Mr. Menzies called the state’s decision to move ahead with Mr. Menzies’ scheduled execution “deeply troubling,” noting “[Mr.] Menzies is a severely brain-damaged, wheelchair-bound, 67-year-old man with dementia and significant memory problems. His dementia is progressive and he is not going to get better.” They have appealed the ruling to the Utah Supreme Court.

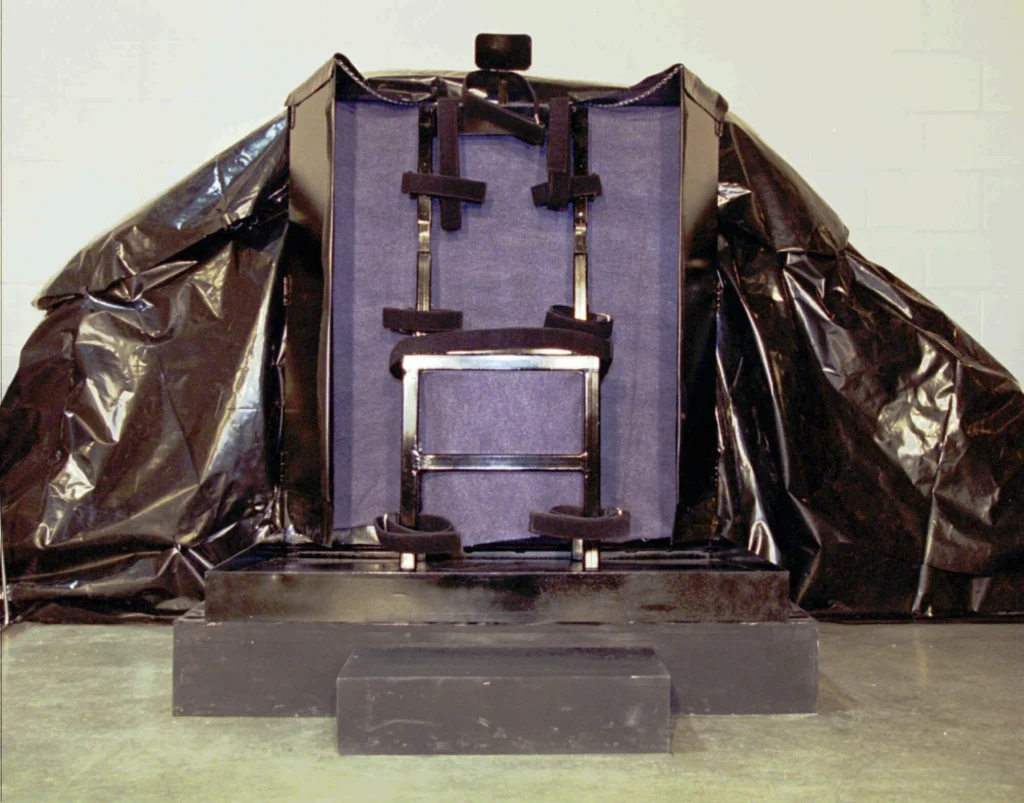

“It is deeply troubling that Utah plans to remove Mr. Menzies from his wheelchair and oxygen tank to strap him into an execution chair and shoot him to death.”

Lindsey Layer, Attorney for Ralph

Navigating through a thick fog is difficult, and people can easily lose their bearings. This reflects how dementia can disrupt a person’s sense of direction and familiarity.

Disorientation: A person with dementia may feel lost even in familiar places or have trouble navigating familiar surroundings.

Social withdrawal: Like someone isolated in a fog, a person with dementia may withdraw from social situations due to communication difficulties and confusion.

This whole situation is frightening. It’s not frightening to Menzies, though, as he has no idea what’s happening to him. It’s only frightening to those who know and love him, to those working tirelessly to save his life, and to those who have a sense of responsibility and respect the rule of law.

Justice Diana Hagen questioned where the line is for a defendant to understand the nature of their crime and the punishment being handed down…

Your honor, there is no pill that one can take to force the defendant to understand the nature of their crime and the punishment being handed down, or meted out. There is no “alarm” that would alert the authorities that Mr. Menzies woke up one morning and was cognizant of all the factors involved here – his crime and the punishment, and how many years he spent wandering through the fog.

For now, he continues, still lost, still wandering….will he wander on September 6th, or will his journey end on September 5th, as ordered by the people who want to kill him?

Donate

OR YOU CAN BUY ME A COFFEE ! (Or a pot of coffee!)

Please be sure to check out my Substack for more articles and commentary on efforts to end the death penalty. If you don’t already, please hit that SUBSCRIBE button, and share!

CLICK THE PICTURE TO GO TO MY SUBSTACK!