Murder In Prison Beside A Ditch

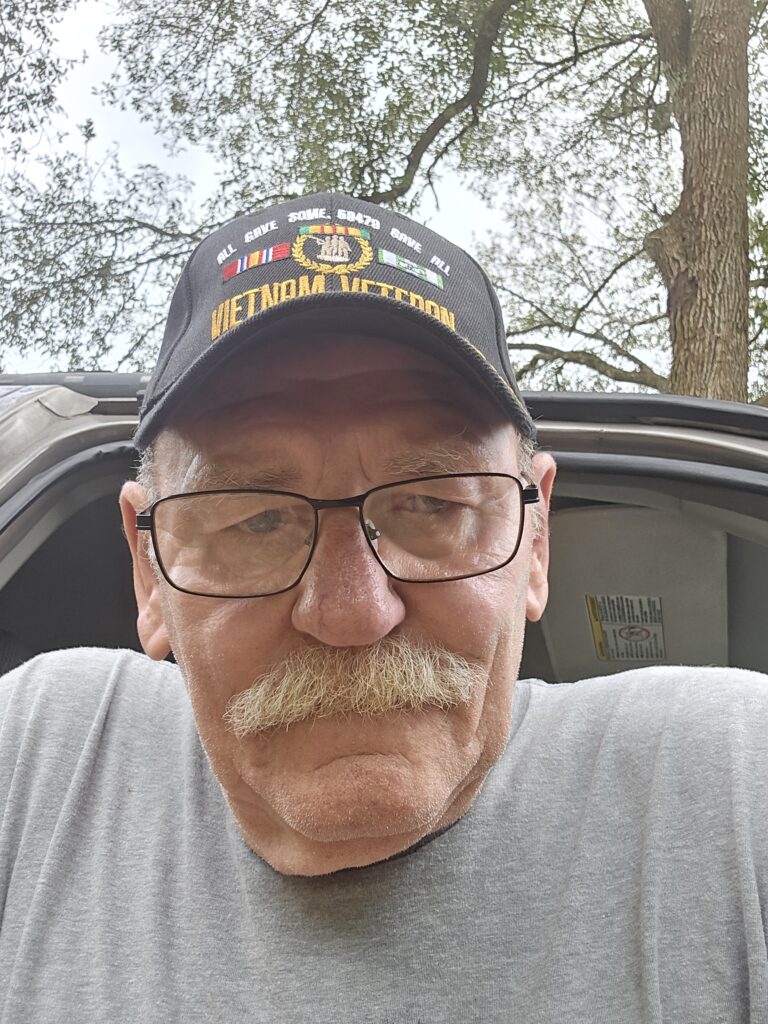

When I first arrived at Angola, it was a truly lawless place, a landscape littered with broken hearts and dreams and shattered souls, a place full of anger and hatred, a place where people went to wait to die. As did I. I was sentenced to LWOP (Life Without Parole) for a senseless murder, the taking of a human life for dollars – chump change, really – in a drug robbery.

Well, now, I did have an excuse though no one wanted to hear it. I was an angry, Vietnam veteran with a humongous chip on my shoulder, mad at the whole world and at the government that didn’t support us and at the people stateside who rallied in the streets to oppose what we were sent to do, where four kids died at our own hands at Kent State University. I was angry at everybody and felt that they all owed me something for my self-inflicted misery.

Angola was still in the throes of integration. Whites and Blacks living together! My God, imagine! And in the heart of the Deep South?! The East Yard was the West Yard and the whole world was crazy. Camp A, Camp F, Camp H, Camp I and Main Prison were the only living areas and they were all a mess. There was none of the Camp C and Camp D and Camp J, they were all lines on blueprints somewhere. DeQuincy was a dream in somebody’s mind because one could never get there. Wade and DCI didn’t exist yet, and the state’s prison population would swell to levels never before imagined. Louisiana has an incarceration rate of 1,067 per 100,000 people (including prisons, jails, immigration detention, and juvenile justice facilities), meaning that it locks up a higher percentage of its people than any independent democratic country on earth.

I spent my first few months at the old RC (Reception Center) building (which housed Death Row and CCR) because about 2 weeks after I got there, Butch Germain got me a job as a clerk in the print shop which was located in the back next to ID. I could pronounce multi-syllable words, could spell, do math and was White. I was a lock for virtually anything. Butch was a guy I met in the backseat of an NOPD cruiser that picked me up from the plane I was extradited from Texas to Louisiana on. Butch was locked up on a Felon in Possession of a Firearm charge, and had copped out for a 10-year sentence on a double-bill to avoid an HFC (Habitual Felony Conviction) sentence. He arrived at Angola about 3 weeks before me, but we had maintained our friendship all during the months of Parish Prison. This, of course, was long before Louisiana went stark raving mad and started issuing 198-year sentences for Armed Robbery and 35-year sentences for Simple Burglary. Much simpler times.

They had gotten rid of khaki-back guards (inmate guards with shotguns) a couple years earlier, though they still utilized them as what we called “Turnkeys.” The only task the Turnkey had was to guard a locked gate and open and close it using a big old heavy brass key. Secretly, they would do a bit of head-thumping for ranking security and always got away with it. The older ones they put in private little rooms on the second floor of RC, and they were protected. I mean, how long would they last in population with guys who just a couple years earlier they had wielded a shotgun over in boiling sun and doing backbreaking labor? Not long, and they knew it. I had an experience with one of those Turnkeys that was pretty entertaining but I’ll save that tale for another time.

About 9 months after I got to Angola, they reopened Camp A following a renovation and 50 of us were the first ones to occupy the Big Stripe side of the Camp. I was the second one through the gate (right behind Chester “Cheeky” Lawrence) and found a choice bunk in the corner and settled in. This was my new home and would be for a couple of years.

For several months we lived in the Camp and rarely went anywhere, rarely saw anything or anyone, and lived an isolated life where simple fights were the norm, “aggravated fights” (with any type of weapon) slightly less common. We didn’t have locker boxes, no way to secure our meager possessions and many fights were over stolen goods, many were over homosexual “lovers” spats, and some were racially motivated. Integration was slow in taking over and becoming the standard. Southern White boys being what they are and Blacks being what they are it kind of took a while for things to settle down.

We kept our possessions in cardboard boxes shoved under our beds, and we had to hustle the boxes from the kitchen or wherever we could find them. The camp was overrun with roaches and silverfish bugs. Radios and 8-track tape players would be infested quickly as the roaches loved the glue on circuit boards. To have a radio – GE Super Radios and Panasonics with a tape player were considered the top of the line – was both a status symbol and an invitation to host a brawl.

We used to gamble – a LOT – because of all the slack time on our hands and no way to burn energy off. For a while we even had a 24-7 poker game on a bunk pushed up next to the bathroom wall so we could see the “table” and count our “money” and pots after the lights were out. There were “big games” and little games. Big games were played with cigarettes, cash, watches, rings, new jeans – whatever one had of value and were worth whatever the “house man” placed on it. Little games were played with cookies, candy bars, and cigarettes.

There had to be guards available to allow us yard time on the tiny patch of land the Big Stripe side afforded. We were fortunate, as the Trusty side didn’t even have a yard – their building looked out on a cattle pen for the dairy which was the main industry of Camp A, but for Trusty prisoners only as they had to be up and at ‘em for 2:00 in the morning. Our back yard was actually big enough to play a raggedy game of touch football and had an old basketball backboard up on a post – sans net, naturally.

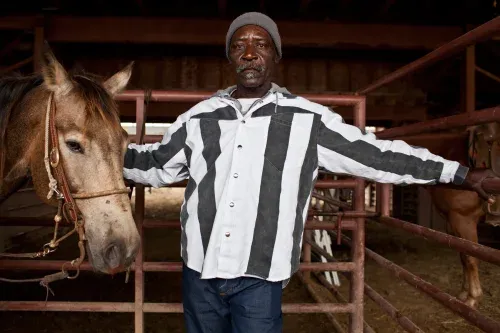

Willie White was in our dorm, and was one of the most fun and bubbly guys you could hope to be around in a maximum security prison. It was almost as if he didn’t deserve to be here, like he had jumped off the bus by accident and never caught a ride back. He and “Big O” were best friends, and Big O liked to put down one of the little poker games because Willie loved cookies and this way they always had a steady supply of duplex cookies for Willie to munch on. Big O was a fat older Black guy and Willie was a short but stocky Black – neither one of them had a racist bone in their body, so some of the White guys would join in their game, myself included.

James Love* was a younger Black guy from New Orleans, a hipster who embodied hip the way Irma Thomas embodied the French Quarter soul sounds she was so well-known for. He was also secretly in a homosexual relationship with “Georgie,” another New Orleans player with what was called “big hair,” an Afro that when fully picked out looked like a huge halo tarnished by time and prison.

This particular day started out just as any other – 65 men rushing to occupy one of 5 ceramic toilets, 4 sinks and a big mop sink. With toothbrushes in hand and clutching sour-smelling washcloths they made their way to the bathroom. Willie was as usual bantering lightly with someone when he encountered Love who said something no one could hear, and Willie turned around and told Love, “Bitch you the one over there making humps up underneath that blanket with Georgie!” Love said something about, “Yeah well, we’ll see about who be making humps!” and walked off.

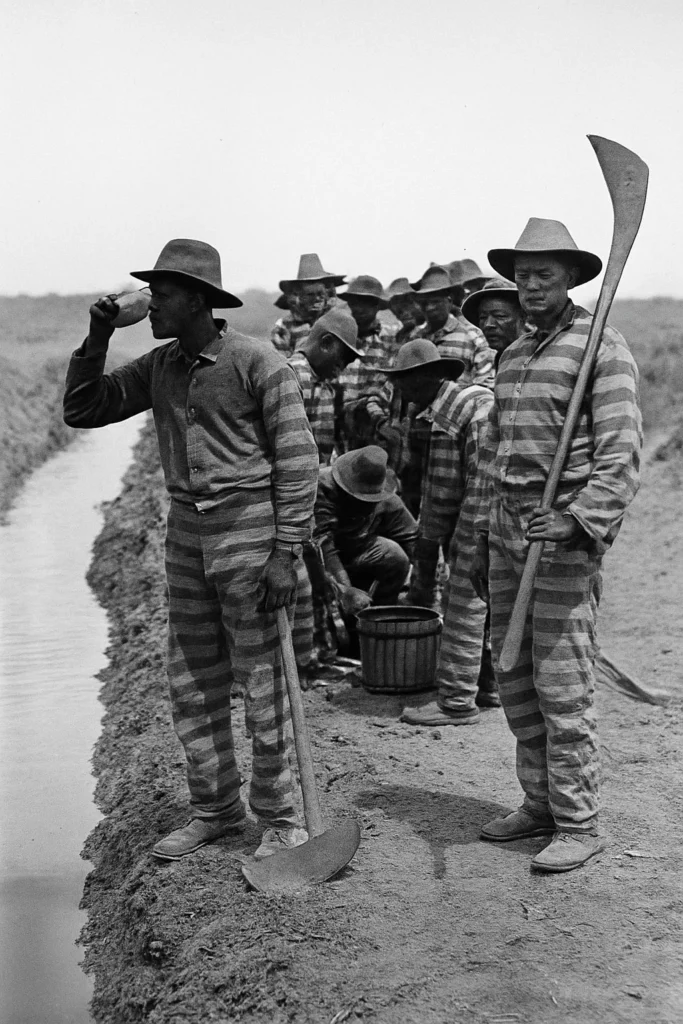

By this time, Camp A had finally gotten an extra free man and he was assigned as a Line Pusher for our dorm’s field squad, Line 2. Because we were a small line (20 men max, as that was the most that a single guard was allowed) we usually worked very close to the camp and always within walking distance. Directly across the main road that ran from the Front Gate of the prison all the way around Angola was a large field where greens were growing. This huge field was surrounded by a ditch about two feet deep by 3 feet wide.

We were clearing the sides of the ditch and the bordering Johnson grass and weeds alongside the road, and using an assortment of tools such as ditchbank blades, a few hoes and a shovel. If you’ve never seen a ditchbank blade, they’re a long-handled tool with about a 14” curved blade about 4”wide. Normally, the Line Pusher would assign one man – a hard worker – to the short blade, which was a typical ditchbank blade but with a sawed off handle, usually used to cut and clear a guard line so the guard had a clear shot down the line.

I was blessed! This was my week to work the water bucket, and my partner was John Blanchard (a little rich White dude out of Lafayette whose daddy owned an oil well service company). The two-man team rotated on a weekly basis. All I had to do was pick the bucket up with John and carry it down to where the free man pointed and set it down. There was a collection of about 8-10 coke cans with holes drilled in the side and a wire hook to hang them from the bucket.

The water wagon would come around to all the lines early in the morning and fill our buckets up and this had to serve the whole line because he wouldn’t come back around until much later. At this time the lines worked for an hour and were given a 3-minute break. During that 3-minutes you had better do everything that needed doing: piss, roll a cigarette, talk, bullshit with your buddies or drink water. At the end of the 3 minutes you immediately went back to work.

When the pusher hollered “Break time! Drain ‘em, get ‘em and roll ‘em,” everybody scrambled, and we headed to the spot he pointed at, just far enough away from him and his horse. We set the bucket down and hung the cans on the lip and stepped back to clear the way for the thirsty workers. After a minute or two, Willie came to the bucket and stuck his blade in the ground and peeled his gloves off and folded them over the handle. He was laughing and joshing with someone as he leaned down and grabbed one of the cans and dipped it into the water.

He was mid-sip— cup to his lips, a casual tilt of his wrist and a laugh still on his lips when the blade came. I didn’t see it at first. Just the cup, slipping from his hand. Just the snap and grunt of his body folding in half like a broken toy. Then the thud. His head – attached only by a cartilage to the body – landed at my feet, eyes still open, mouth still curved in the soft shape of a swallow.

The blood came in a sudden burst—hot, blinding, metallic. It painted my shirt, my face, my mouth. I staggered back, gagging, hearing the distant echo of my own scream tangled with eighteen others. The Line Pusher was frozen with a look of horror on his face, and he drew his weapon and shouted and choked and put his pistol back in the holster, then drew it again and tried again to get his words out and failed.

Eighteen men—tough men, hard men—frozen mid-roll, mid-joke, mid-breath. Someone dropped a half-rolled cigarette. Another vomited instantly. No one moved toward the body. No one dared. It was as if time had cracked open and spilled something ancient and merciless into our midst. One moment: laughter, cool water, early morning weariness and sweat. The next: death, unfiltered and grotesque, as intimate as breath on skin.

No warning. No reasoning. Just the bright red of carotid arterial blood. Just silence. Just the sound of the cup tumbling slowly across the dirt, as if trying to pretend this was still just a normal working day.

Love stuck his short blade in the ground and walked to the ditch, away from our circle of shock and away from the Pusher. When he got to the ditch, he simply sat down. No drama, no excited yelling, just a weary sigh as if he had completed some long-burdensome task.

This was, of course, long before Angola had millions of dollars worth of 2-way radios and broadcast towers and computerized communications networks and ambulances. In those days, emergencies were broadcast from the fields by a succession of three quick gunshots that signaled what was known as a high-rider. Depending on his location, he would be either on horseback or riding what we called a “bronco,” which was akin to a Jeep.

We were still trying to gather our wits when the air was shattered by his three rapid shots. Moments later the high-rider screeched to a stop and he jumped out and asked the pusher what was happening and his eyes followed the pusher’s silent, shaky pointing finger. His eyes widening, he drew his weapon and screamed at everybody to move toward the middle of the field and away from the scene.

Within a half-hour there were a half-dozen or more broncos and personal vehicles gathered around us and they began pulling us off to the side and questioning us as to what we had seen or knew about what had happened. Love was handcuffed and hauled off to whatever fate awaited him, and after another hour or so we were lined up and counted and walked back to the camp. I don’t know what everybody else said, but I didn’t see anything.

The mood was subdued, somber. Everybody was quiet. We got to the gate and the shakedown was a lot more thorough than usual, and there were a lot of “mother fuckers” thrown around, Upstairs, we watched quietly as the guards came and packed up both Willie’s and Love’s property and left without another word.

The next day was a normal day.

I told this story because I was talking to my friend and extraordinary filmmaker and documentarian, Catherine Legge, on the phone yesterday about the violence in Angola and this story came to mind. It was my first witness of a murder in the prison and it had a lasting effect on me. From that point forward I kept a proverbial set of eyes in the back of my head.

For 47 years I held on to those eyes, as if they would be the only thing that would save me. They probably were.

This was the first murder I witnessed in Angola, but it wouldn’t be the last. Thank God it is a different world today.