And where it comes from…

What IS trauma?

Trauma is defined as an emotional, psychological, or physical response to an event or series of events that are distressing or harmful, often overwhelming a person’s ability to cope.

This can include experiences such as violence, sexual abuse or physical abuse, accidents, or natural disasters that lead to feelings of intense fear, helplessness, or horror.

Trauma can manifest in various ways, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), affecting an individual’s daily life, relationships, and overall mental health.

Understanding trauma is essential, especially in contexts like prisons, where individuals may face unique and compounding challenges that amplify their experiences of distress.

Here’s another question:

Does prison lead to trauma, or does trauma lead to prison? I think that in the majority of cases, trauma leads to prison…but prison ALWAYS leads to more trauma.

Trauma significantly influences why some people end up in prison. It often leads to harmful behaviors and poor coping skills. Experiencing violence, abuse, or serious neglect can warp a person’s self-view and how they see the world, leading to increased anxiety, aggression, or impulsive actions.

These traumatic events may push some to commit crimes for survival or to regain a sense of control. Furthermore, the lack of mental health resources and support can leave traumatized individuals without the means to heal, making them more susceptible to the justice system. In essence, unresolved trauma can create a tough cycle to break, contributing to the high number of traumatized people in prisons.

Trauma often leads to harmful behaviors and poor coping skills.

Trauma often has its origins in adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse within the home, unstable family structures like single-parent households, exposure to substance abuse, and community crime.

A young child growing up in such an environment may first feel unsafe and neglected, leading to emotional and behavioral issues. As they transition into adolescence, feelings of abandonment or rage may take hold, oftentimes impairing their ability to form healthy relationships and cope with stress.

If these individuals begin seeking “unhealthy” outlets—such as engaging in drug use or alcohol or associating with delinquent peers—they may further spiral into risky behaviors. This cycle of trauma can escalate, leading them into criminal activities as a means of survival or providing an escape. The compounded effects of untreated trauma can create a firmly entrenched path, ultimately steering them toward the criminal justice system and incarceration.

Home to School to Prison…and the Pipeline There

The “home to school” path for a child experiencing trauma is critical in understanding how environments influence their emotional and psychological well-being. For many children, home life can be a source of significant distress due to factors such as domestic violence, neglect, substance abuse, or instability. In the beginning, school may represent a refuge from these challenges, offering a comforting structure, a form of social interaction, and offering the potential for academic success.

Upon arriving at school, however, the child’s experience may be very complex. Some children find school to be a safe haven, as it allows them to escape the traumatic conditions at home, even if temporarily. In these instances, the structure provided by a school environment can facilitate healing in that it gives children a space where they can engage with peers and, as importantly, caring adults, which is essential for their emotional development.

Conversely, for some children, school can present a new set of challenges that may reinforce existing trauma. Factors such as bullying, academic pressure, social isolation, or rigid disciplinary practices can turn school, at first a refuge, into a traumatic environment. This contradiction can lead to heightened anxiety and distress, making the journey from home to school fraught with tension rather than relief.

Additionally, trauma can deeply affect a child’s ability to engage with their environment. Symptoms such as hyper-vigilance, emotional dysfunction, or difficulties in forming relationships can affect how a child interacts with teachers and fellow students. These challenges can create a cycle of trauma, where the child feels unsafe both at home and in school, reinforcing that sense of vulnerability and isolation.

So, the “home to school” path is not a straightforward and clear transition. It often involves a complex interplay of escaping one form of trauma only to potentially face another. In some cases, the traumatized child will find comfort in structured learning. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for educators and advocates in creating supportive school environments that recognize and address the broader impacts of trauma on children.

Is School a Refuge – Or a Place of More Trauma?

And, School To Prison…The “school to prison pipeline” is a complex phenomenon where students, particularly those from marginalized communities, face disciplinary actions in schools that often lead to law enforcement involvement. For a child already experiencing trauma—whether from economic instability, domestic violence, or community violence, or abuse—the pressures of this pipeline are magnified.

Traumatized children may exhibit behaviors such as aggression, withdrawal, or defiance, which are often misinterpreted by educators. Instead of receiving support, they may face harsh disciplinary measures, such as suspensions or expulsions. This pushes them further away from education. Factors such as lack of access to mental health resources, negative school climates, and socio-economic disparities can lead these children to feel alienated and disengaged. This only increases their chances of indulging in criminal activity as a way to cope or seek validation. Understanding these connections is crucial for developing interventions that address the root causes of behavior rather than simply reacting to the symptoms.

How does this progression work in real life? Let’s meet Marcus.

A young boy named Marcus grew up in a home filled with domestic violence, often witnessing his parents fight, his father often beating his mother. This led to him feeling emotionally neglected and very alone. The unstable home life caused him to struggle in school, making it hard to focus on his classes and to connect with fellow students. Failing to make this connection led to bullying. Frustrated and helpless, Marcus acted out by skipping classes and hanging out with older “friends” who seemed to understand his pain. He was soon engaging in petty theft. His rebellious behavior escalated, and he was eventually caught vandalizing school property, resulting in a troubling encounter with police.

Instead of receiving the support he needed, he was labeled a delinquent. Each time he came into contact with the authorities, his trauma deepened. This led to an arrest that put him on a path toward prison, continuing the cycle of trauma that started at home.

JUVENILE COURT PROCEEDINGS

Traumatized children may exhibit behaviors such as aggression, withdrawal, or defiance, which are often misinterpreted by educators. Instead of receiving support, they may face harsh disciplinary measures, such as suspensions or expulsions. This pushes them further away from education. Factors such as lack of access to mental health resources, negative school climates, and socio-economic disparities can lead these children to feel alienated and disengaged. This only increases their chances of indulging in criminal activity as a way to cope or seek validation. Understanding these connections is crucial for developing interventions that address the root causes of behavior rather than simply reacting to the symptoms.

JUVENILE COURT PROCEEDINGS

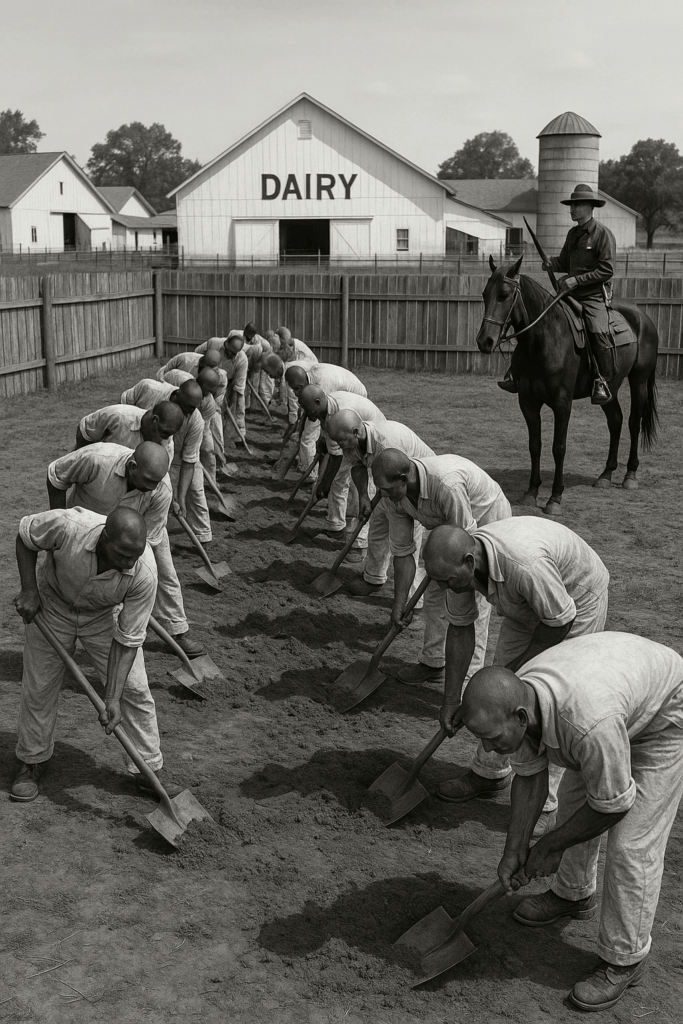

PRISON…And More Trauma

What would have been the right time to intervene? What type of intervention would have been successful? Whose intervention would have been most valuable?

We will never be able to know. Marcus’ life continued to spiral out of control after he went to prison. By the time someone took the time and made the effort to intervene in his life, to attempt to get him to confront and defeat his trauma, it was too late. Marcus died of an overdose of fentanyl, alone, in a cell, in prison.

THIS is what “trauma” is, and what it does.

Below, you will find links to resources that may be of help. If trauma begins at home, that’s where it should be treated. Thank you for reading this!

RESOURCES WHEN THERE IS AN INCARCERATED PARENT

This post is dedicated to an unnamed Assistant Warden at Angola, who asked me to write about trauma, because they understand what trauma does, and where it leads.

Donate

DONATE TO MY LIFE AFTER PRISON

OR YOU CAN BUY ME A COFFEE ! (Or a pot of coffee!)

Please be sure to check out my Substack for more articles and commentary on efforts to end the death penalty. If you don’t already, please hit that SUBSCRIBE button, and share!

CLICK THE PICTURE TO GO TO MY SUBSTACK!